“I am too stiff to do yoga” must be the most common argument I hear from people who say they are interested in yoga but have never tried it. Of course, they could just be giving me a polite reason not to take a class but not practising yoga because of inflexibility may be the poorest excuse out there. Not only will yoga help improve your range of flexibility but in fact, being ‘stiff’ may prove to be an asset in your practice.

In this article we’ll look at what we really mean by stretching, the role of fascia and muscles and how we can get the benefits of yoga and movement without “overstretching” our bodies.

In the media and also among yoga classes and teachers, there is a huge emphasis on flexibility. So much so that it seems like a prerequisite to starting yoga. There are very few yoga teachers in the public eye that cannot do a full split or bend in a pretzel shape. We now seem to have created the situation where flexibility equals being a good yoga practitioner or teacher. For a long time I also believed this to be true. I have come a long way since then, and feel like maybe it is time to start countering this widely held belief.

We seem to have created the situation where flexibility is a prerequisite to being a good yoga practitioner or teacher… I think it is time to start countering this widely held belief.

I have been a yoga teacher for almost 15 years. Yoga is an integral part of my life. Yoga has made me very flexible and has had a good and healthy impact on my body and soul overall. Granted, being “bendy” looks good in photos and people are impressed that I can reach beyond my toes. But whether or not that equals ‘good yoga’ is another question.

No pain, no gain

Over the years, over-stretching my body has been the cause of numerous yoga-induced injuries. I have had so many I can hardly count them: over-stretched inner thighs, hamstrings, shoulders, and so on. For over six years, my overused and overstretched psoas caused radiating pain in my torso and lower back. All those years I tried to heal myself by aligning, strengthening and practising yoga. Then it occurred to me I might be doing too much; too much yoga and way too much stretching.

Most ancient yoga teachings don’t advise taking yoga to the extreme. Doug Keller, an expert in yoga therapy and yoga philosophy and history, states that Tantric yoga scriptures teach moderation. This moderation applies to every aspect of life: eating, socialising, meditating, practising asana. This wisdom does not appear to have carried over into the modern day view on mainstream yoga. We are bombarded with images of yogis in ever more extreme poses looking very radiant and peaceful. These images seem to suggest that the more you practise, the more flexible you become, the better yogi you are and the happier you will be. But if we take a closer look you may be shocked to learn this may not hold true. Let’s take a look at the technicalities and effects of stretching the body.

What is ‘stretching’ anyway?

Stretching is a word that fascia expert Tom Meyers doesn’t like; technically it is not something that you are doing. In performing a yoga pose, you are exerting strain on (various parts of) your body. This strain is distributed along certain lines and pulls on the muscles, tissues and joints along a network of connective tissue. To really understand what we are doing, we need to make a distinction between putting strain on the muscles and the fascia, or connective tissue.

When coming into a stretch, the body responds first by a freeze reaction, known as the ‘stretch reflex’, in which the muscles initially protest against the strain. Depending on your condition and routine, this strain releases after about one to three minutes. Muscle is elastic by nature and when the stretch reflex subsides and the fibres of the muscle release, the muscle will go to a more lengthened state. This is the normal expansion and contraction of a muscle and therefore is not really a ‘stretch’. Once the ‘stretch’ is over, the muscle will contract again to its natural state. So nothing much has really structurally changed in the muscle.

However, it is different story with the connective tissue. After the stretch reflex releases, the fibres of connective tissue, which are less elastic, will start to ‘glide’ to a more extended, more lengthened state. In contrast to the muscles, the connective tissue fibres re-attach in this extended state. Connective tissue stretches in a way somewhat similar to how plastic stretches; if done slowly and evenly, the fibres will come into a new form or shape and keep that shape. But if done too quickly or unevenly, the plastic will tear. But to keep it simple; we will use the term ‘stretching’ to describe this process of altering the form of the body.

Types of fascia

Fascia is found everywhere in the body. It holds your skeleton together, encases your organs, nerves and muscles. It is even found in your eyes! Fascia also exchanges information to the brain through the many nerves that run through the tissue. For the yoga practitioner, three types of fascia are important to keep in mind: the ligaments, the tendons and myofascia:

- The ligaments are connective tissue that connects your bones. This tissue is very fibrous, strong and inelastic and meant to hold bones together and stabilise the joints.

- The tendons connect the muscles in your body to the bones or connect muscle to muscle. This fascia is less thick and fibrous, and is less inelastic, but is also not meant to stretch.

- Myofascia runs through your muscles and encases your muscles in compartments, much like an orange having different parts. The myofascia holds the muscle bundles together.

Benefits of stretching

Stretching your body is a good thing. It is healthy for the muscles to be stretched and the myofascia to be under tension, especially when the body is well aligned. Stretching promotes circulation and therefore keeps the joints and muscles flexible and juicy and keeps the body supple and vibrant. In addition, connective tissue is responsible for your body awareness. Supple and hydrated fascia give you a sense of spaciousness and connectedness to your body as the nerves in the fascia can optimally communicate with your brain. Furthermore, the connective tissue in your body is also partly responsible for your proprioception, your body’s sense of where it is in space and how it relates to itself. The practice of yoga and stretching muscles certainly contribute to body awareness and overall good health. But you can also enjoy these benefits without being able to put your legs behind your head.

The practice of yoga and stretching muscles certainly contributes to body awareness and overall good health. But you can also enjoy these benefits without being able to put your legs behind your head.

Overstretching

Sometimes in class, when I see my students struggling to grab their toes in Paschimottanasana (Seated Forward Fold), I jokingly remind them: “There is no prize; you will not get enlightened when you reach your toes”. Although that usually gets a chuckle or two, students rarely back off and continue to try to pull themselves deeper into the pose, to stretch beyond where they are.

In my experience, flexible people are in general more at risk of injuring themselves than stiff people when practising yoga. Many bendy students have a tendency to bypass a core stability and integrity in their body, When stretching in a yoga pose, the strain is not isolated, but pulls on a whole system of connective tissue, which leaves them vulnerable to overstretching of the weaker parts. This can lead to nasty and sometimes chronic situations, which I have seen a few of in my years of teaching. Yoga practitioners striving for more and more flexibility increase their risk of tendon, ligament and joint overstretching, with many consequences.

The potential damage

Every time you experience “sore muscles” after yoga or exercise, you have torn muscle fibres. Micro tears in the muscles are normal with exercise and heal quickly. Muscles have good blood flow which allows regenerating cells to work efficiently and fast. These micro muscle tears are different from tendon tears, which are quite common in yoga because of overstretching. This type of tear takes a lot longer to heal (up to a year is not uncommon). Overstretching ligaments takes the damage one step further and in some cases can lead to chronically unstable joints. Too much pulling on the joints when stretching is probably the riskiest kind of overdoing it and the one that has the longest lasting effect on the body.

A common example of overstretched tendons and ligaments are hamstring attachment tears, also known as ‘yoga butt’. This is quite common and often caused by extreme forward bending or hip flexion poses, such as Uttanasana (standing forward bends) or Paschimottanasana (Seated Forward Fold) variations or asymmetrical hamstring stretches such as Utthita Hasta Padangustasana (Extended Standing Hand to Big Toe pose).

An example of ligament over-stretching is overstretching the legs in poses that put the sacroiliac (SI) joint (between the two sides of the sacrum at the back of the pelvis) or the lower back under too much pressure. The SI joint can then dislocate and cause a host of problems in both the legs and the spine, such as radiating pain in the pelvic area or sciatic nerve pain. This can be caused by extreme stretching in variations of Eka Pada Rajakapotasana (One-Legged King Pigeon pose) or Ardha Matsyendrasana (Half Seated Spinal Twist).

When less flexible fascia is a benefit

Many teachers have only limited knowledge about the potential dangers of stretching and so may encourage students to move deeper into a pose than what may be healthy for them.

Having stiff muscles, or more accurately less flexible fascia, constricts your mobility and at the same time protects your joints and ligaments from overexertion. The stability of your body protects you against injuries like the ones I described above. You may never do a full split, but you will probably never destabilize your sacroiliac joint either. So the next time you are encouraged to stretch yourself beyond your limit, stop for a moment and consider what you are trying to achieve.

Honour your yoga body

While it may seem otherwise, it is not my intention to scare you away from yoga with this article. The benefits of practising largely outweigh the risks associated with the practice. It’s not the practice of yoga that is the issue, but how we practise yoga. We can get so fixated on getting somewhere, becoming something, that we bypass ourselves and unconsciously put our health at risk.

It’s not the practice of yoga that is the issue, but how we practise yoga. We can get so fixated on getting somewhere, becoming something, that we bypass ourselves and unconsciously put our health at risk.

We tend to forget that the most valuable part of our yoga practice is simply listening to our bodies. There is no such thing as ‘a yoga body’. There is just your body. And that body is perfect for yoga.

Tips to remember when stretching:

Listen: pay attention and relax. Try to feel your body before going into active stretching. Do you notice any compression in parts of your body? Are your joints open or locked? Do parts of your body feel vulnerable or sensitive? Are you holding your breath and tension in your body? The better you listen to your body, the better you learn to stretch.

Align: feel and root down through your bones and skeleton. Muscles work most optimally when the bones are well aligned in their joints. Aligning the bones will reduce unnecessary tension because you primarily rely on the stability of your skeleton rather than your muscular system. Keep all your joints open not locked; in particular, knees, wrists, elbows, shoulders and spine.

Go slowly: over-stretching is easily done when you rush into the pose. When you are in a hurry, is this because you are not fully present and attentive (see #1)? Are you bringing your stressful office day onto your mat? Or is it because the pose is maybe a bit beyond your ability and you want to do it anyway? Going slowly allows you to see your motivation more clearly and shows you where your limits are.

Boundaries: work within your limits, not right up to or over them. You have two edges – a hard edge and a soft edge. Work in the space between these two boundaries. Doing so will enable you to stretch for a longer period of time (this increases the chance of creating structural change) and keeps your body safer in the pose.

Use props: props are largely considered by yogis to be for the inexperienced practitioner or only used “when you cannot properly do yoga”. You can do yourself a big favour by dropping the arguments you may have against props. Props are your friend; they help you to feel more (like a block between the inner thighs), to support you and give stability. People come in all different sizes and dimensions – yogis too! If you have long legs and shorter arms using two blocks in Uttanasana (Standing Forward Bend) is just using common sense.

Engage: in a dynamic, active class, always, always engage your muscles to stabilize your joints and muscles before actively stretching your body. Many injuries stem from the lack of proper engagement in the body. Activation of your muscles compresses the muscle fibers so the muscle becomes shorter, which reduces the risk of unsafe stretching.

Enjoy: how do you feel in the pose and in the stretch? Are you struggling? Are you bored? Or does the pose make you feel vibrant and alive? Enjoying and feeling pleasure in your body is the reason a yoga practice is so deliciously juicy! Safe stretching is a big part of that. When you stretch, there may be a feeling of opening part of you that has not been seen for a while, that has not moved and feels numb or stuck. Addressing these parts of your body should be a very satisfying aspect of your practice and a motivator to come back to your practice again and again.

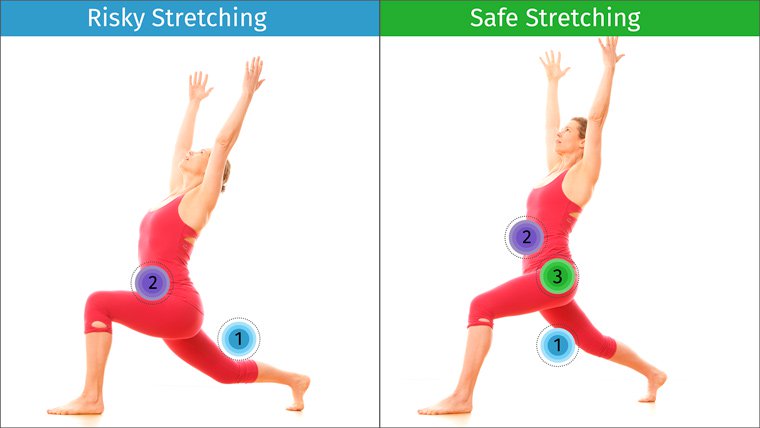

Stretching the hips in standing poses

Risky stretching

- “Hanging” in the hips by allowing the back leg to drop to the floor creates unbalanced tension in the hip flexors.

- This “hanging” potentially compresses the sacroiliac joint when stretching.

Safe stretching

- Draw the legs to the midline and lift the back leg to create a safe stretch in the hip flexors.

- Engage the lower belly muscles to align the pelvis and sacrum.

- Now, from the center of the pelvis, stretch out through both legs and up through the spine.

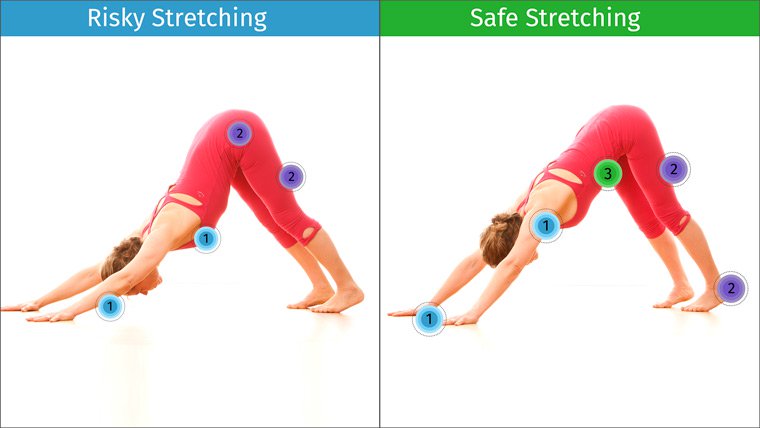

Stretching in Adho Mukha Svanasana

Risky stretching

- Dropping the arms toward the floor while pressing the chest down and “hanging” in the shoulders pulls the shoulder blades off the back ribcage. This compresses the shoulder joints and can be damaging to the rotator cuff muscles.

- Lack of muscular engagement in the legs and excessive forward tilt of the pelvis exposes the hamstrings to overstretching.

Safe stretching

- Press the hands evenly into the floor to engage the arm muscles in a balanced way. From the hands draw the muscles up “into the shoulders”.

- Press your feet into the floor and engage the leg muscles, pressing the tops of the thigh bones and sit bones back.

- Then draw the belly in and from the sternum stretch out to the hands and to the feet.

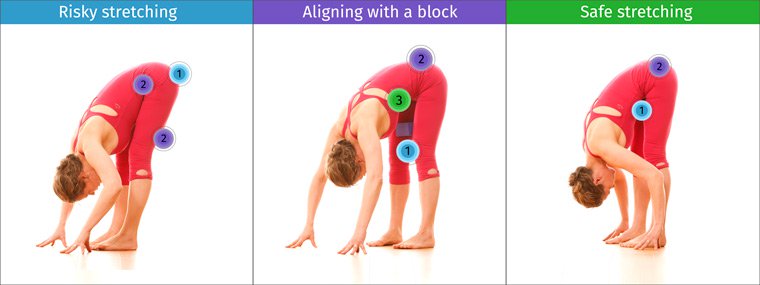

Stretching in Uttanasana

Risky stretching

- When the pelvis is behind the ankles it promotes “hanging” in the pelvis and hamstrings.

- This misalignment and lack of muscular engagement compresses the hip flexors, creates excessive pressure in the sacroiliac joint and increases the risk of overstretching in the back of the legs and pelvis.

Aligning with a block

- Bring the pelvis directly over your feet. Use a block to engage the inner thighs, “hug into your midline” and activate the leg muscles.

- Keep the knees soft and press the (inner) thighs and sit bones back until the pelvis tips forward and the sacrum is the highest point in the pose. For people with tighter hamstrings and inner thighs, bend the knees as much as needed until the forward tilt happens.

- Draw the lower belly in and hug the outer hips, until you feel a “lift” in the front body.

Safe stretching

- Keep this alignment and stability in the legs, outer hips and belly.

- Now press down from the centre of your pelvis to your feet and from the pelvis lengthen through your spine and crown of your head.

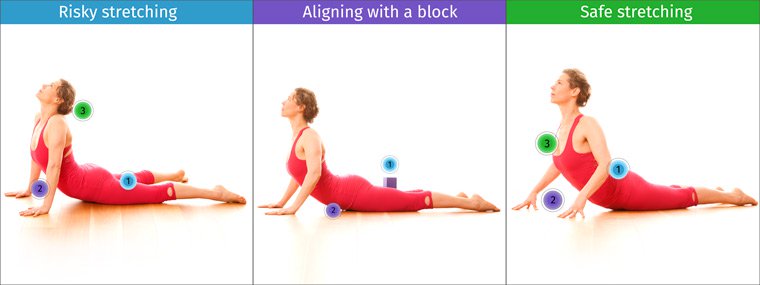

Stretching in Bhujangasana

Risky stretching

- Lack of muscular engagement in the inner thigh muscles, separates the legs away from the midline, compresses the sacrum and creates excessive lumbar extension (arching).

- Unengaged hand and arm muscles build up pressure in the wrist joints and allows the arm bones to move to the front of the body. This creates compression in the shoulder joint and upper back.

- Pressing the head into the neck creates compression in the neck and overstretching in the throat.

Aligning with a block

- Use a block between the inner thighs to help create stability in the core line of the body. Activate your inner thighs by pressing into the block and “roll” the leg bones inward. This helps to align the legs, the pelvis and the lower back.

- To protect and stabilize the lower back in the backbend, draw the lower belly muscles in.

Safe stretching

- Keep the alignment and stability in the legs. Lengthen the sides of your waistline and release your shoulders down. From your pelvis stretch out evenly through legs and spine.

- Press the hands (or fingertips) into the floor and activate the arm muscles from the hands into the shoulders. Draw the shoulder blades onto the back.

- From the engaged arms and legs and core, now move your chest forward (not straight up!) between your arms.