As some of you may have spotted by now one of my major passions is teaching anatomy and SAFE yoga so that we may continue our practice long into old age!

In this article I wanted to take a closer look at the anatomy of shoulders and how we can use this knowledge to keep them safe in Chaturanga Dandasana – a pose sometimes seen as the culprit of many yoga injuries. We’ll begin with a run-through of the main muscles around the shoulder, how they can end up being misaligned, and how to use the muscles to integrate the shoulder joint to keep it healthy and safe in our yoga practice.

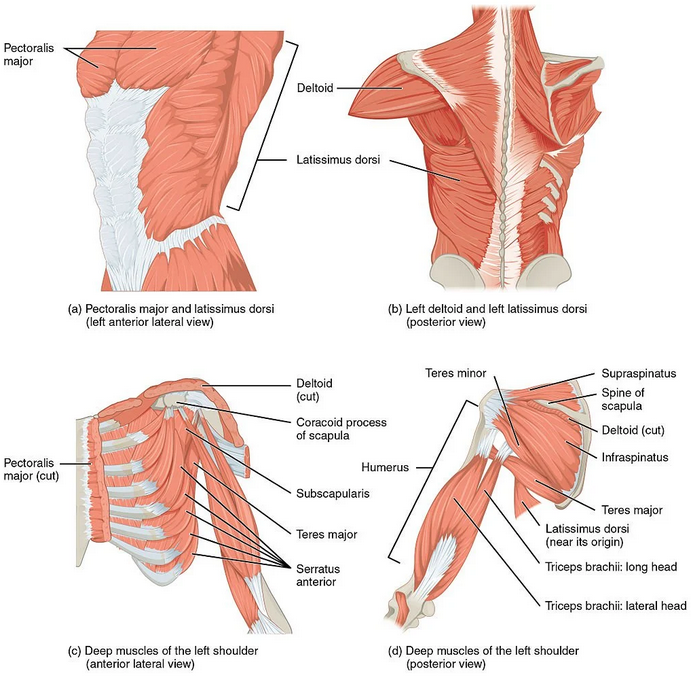

Who’s who in the shoulder? Three bones and a lot of muscles!

Let’s start with a bit of anatomy. While the hip joint is designed for its stability, the shoulder girdle is known more for its mobility. It is a spacious, shallow joint made up of three bones:

Scapula (shoulder blade) Clavicle (collar bone) and Humerus (upper arm bone).

There are many different muscles at work in the shoulder girdle; either holding the three bones together or moving them. We can group these into three categories:

Rotator cuff muscles – These muscles attach the upper arm bone into the joint created by the collar bone and the shoulder blade. They also move the arm sideways away from the body (as if flapping a wing) and rotate the arm in two different directions.

Muscles that move the humerus bone (but are not attached to the scapula), and;

Muscles that move the scapula

Rotator cuff muscles

| Muscle | Main action | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Supraspinatus | humerus abduction | lift your arms out to the side |

| Infraspinatus & Teres Minor | humerus external rotation | twist your arms with your knuckles facing backward |

| Subscapularis | humerus internal rotation | twist your arms with your knuckles facing forward |

Muscles that move the humerus bone (but are not attached to the scapula)

| Muscle | Main action | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pectoralis Major | abduction of humerus in flexed position | start with your arms straight out in front and bring your palms together |

| Latissimus Dorsi | adducting humerus to side body | with your arms out in a T shape, lower them to your sides |

| Lateral Deltoid | adduction of humerus (with supraspinatus) | with your arms at your side, raise them to a T shape |

| Anterior Deltoid | flexion of humerus | with your arms by your sides, raise them up in front of you |

| Posterior Deltoid | extension of humerus | with your arms by your sides, bring them behind you (as if clasping your hands behind your back) |

Muscles that move the scapula

| Muscle | Main action | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pectoralis Minor | anterior and inferior tipping of scapula (if the ribs are not moving) | tilting the top of the shoulder forward and down |

| Serratus Anterior | protraction of scapula | forward rounding of the shoulders |

| Levator Scapula & Upper Trapezius | elevation of scapula | lifting your shoulders to your ears |

| Rhomboids & Mid-Trapezius | retraction of scapula | drawing the shoulder blades towards each other |

| Lower Trapezius | depression of scapula | pressing your shoulders down |

Looking at the number of muscles that move and hold the bones together it is no wonder that there are complicated anatomical relationships going on!

Common habitual patterns and shoulder misalignments

Due to the fact that most of modern-day society lives in the flexion portion of the sagittal plane (think driving, sitting, typing etc) we can experience a lot of imbalance between pairs of muscles eventually leading to misalignments in the body. The muscles on the front body become “tight” as in limited in their range of motion.

Working on computers for too long without breaks can lead to tight, locked-short pectorals and serratus anterior muscles, which then leads to tight, locked-long rhomboids, mid and lower trapezius muscles on the back. The accumulated years of typing can eventually lead to tight, locked-short internal rotators (subscapularis) and tight, locked-long external rotators (infraspinatus).

Hunching up our shoulders because of stress and/or cold weather can lead to tight, locked-short upper trapezius and tight, locked-long lower trapezius.

Added to this, unless we take up activities like climbing or rowing we have far fewer pulling than pushing actions in our daily lives. This can also lead to weak rhomboids and latissimus dorsi muscles.

All of these habitual patterns can eventually lead to imbalance and instability in the body, putting yogis at a higher potential risk of injury if they are not acknowledged and worked with. This is especially so when practicing repetitive weight-bearing poses, such as Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-limb Staff pose, Vasisthasana (Side Plank), Bakasana (Crow pose) and Adho Mukha Vrksasana (Handstand).

Applying this knowledge to Chaturanga Dandasana

Shoulder joint integration: 4 key muscles for a “Perfect” Chaturanga Dandasana

The scapula-clavicle-humerus joint and its extremities are all connected to the axial skeleton by the one ligament at the sternoclavicular joint. If we repeatedly practice Chaturanga Dandasana without proper joint integration the ligament of this joint can be seriously damaged – overstretched to the point of no return.

By “proper joint integration” I mean that you “plug” the humerus into the spacious and shallow joint of the shoulder and at the same time slightly protract the scapula so it “plugs” into the ribcage without collapsing into the chest. In order to do this efficiently, effectively and safely, there are many muscles that need to be working together.

The four main muscles are:

- Latissimus dorsi draws the humerus in so that the head of the humerus can be in line with the distal end (the elbow joint),

- Infraspinatus externally rotates the head of the humerus in the joint socket (plugging it in),

- Serratus anterior protracts the scapula wide onto ribcage, and;

- Lower trapezius depresses the scapula (taking the shoulders away from the ears). This dance between these four muscles is a complicated, yet so rewarding one when done with awareness and executed deliberately with the aide of the breath.

What about the rhomboids in Chaturanga Dandasana?

I hear many yoga teachers teach students to engage the rhomboids when performing Chaturanga Dandasana, but rhomboids are adductors/retractors of the scapula and encourage the experience of “backbending” in the thoracic spine.

However, even though I see this as incorrect cuing, the reasoning for it is spot on: tight pectorals, upper trapezius and subscapularis muscles from life’s habitual patterns have most new practitioner’s over-doming in their upper back and collapsing into rounded shoulders. People are literally dumping into their chests in Chaturanga (with elbows winged far out) and shredding their shoulder connective tissue in the process.

Engaging the muscle fibres of the rhomboids, along with mid-trapezius, does effectively help to stretch the pectoralis major muscles. And in backbends the rhomboids are perfect agonists to stretch the antagonists of the pectorals. In Chaturanga Dandasana though, we don’t want to be backbending while hovering parallel to the floor as the chest will dip below the head of the humerus or the ribs come below the parallel upper arm. This puts too much pressure on the sternoclavicular and the acromioclavicular ligaments.

Instead, it is best to focus on stretching/releasing the tight pectoralis minor by actively engaging the lower trapezius muscle fibres. These draw the scapula down the back towards the hips – helping to free the clavicle area of unnecessary and possibly injurious tension and compression.

To bring the elbows in or to not bring the elbows in…that is the question

Many questions arriving in my inbox of late have been in response to a YouTube video circulating which promotes the idea that yoga teachers over cue “elbows in” when practicing Chaturanga Dandasana. I myself used to say in the past “Elbows in, as if elastic bands were attached from your elbows to your ribcage”.

My response is yes, it is true that these sorts of cues do not work for every body type. In a “perfect” Chaturanga, you need the latissimus dorsi to draw the elbow in line with the head of the humerus supporting the most beneficial alignment of the hinge joint of the elbow (versus winging out or winging in and putting too much strain on the connective tissue). For some yoga practitioners, their shoulders are broader than their waists/ribcage area: if this body type were to bring their elbows into their side waist/ribcage area they would be out of alignment, putting undo strain on both the shoulder girdle and the elbow. So the full version of the cue would be “activate and engage the latissimus dorsi to bring the elbow in line with the head of the humerus!” and then follow with “plug upper arms into their socket with infraspinatus, draw shoulders away from ears with lower trapezius, and broaden shoulder blades across back with serratus anterior muscles”. Which is a mouthful to say during the middle of a Vinyasa flow class of course! But only serves to highlight the need for enough time to be given to teach and practice Chaturanga Dandasana as a pose in its own right outside of the Vinyasa flow sequence as well. Take a look at my class linked below for some Chaturanga “homework”!

SAFE YOGA ROCKS: On-the-mat injury prevention leads to an off-the-mat happy life

For the modern day Vinyasa yoga practitioner, powerful and dynamic flow yoga is meant to support busy and chaotic, although often rewarding, lifestyles off the mat. In this style of yoga there is much repetitive motion in weight bearing/load bearing postures (often with fast and possibly injurious transitions). In order for us to continue to gain the multitude of benefits this style of Hatha yoga offers for the health of the systems of the body as well as the inner workings of the mind, working with breath, bandhas, bone alignment, proper muscle activation and joint integration is not only key but a must! Especially in the area of the shoulder girdle – a complicated joint known not so much for its stability but more for its mobility!

For more on preventing yoga injuries please take a look at my five-part series of articles on the topic. Starting with the Breath, Prana and the Vayus.

A class for EkhartYoga members

Want a Perfect Chaturanga? Here’s some homework – Vinyasa Flow with Jennilee Toner, 30 minutes, all levels.

Image of the shoulder muscles by OpenStax College [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@6.27.